Web Exclusive: Playing by the Rules Pays Off

Following procedure and ensuring documentation during the high-profile Autumn Pasquale case safeguarded a New Jersey Child Abduction Response Team (CART) from wrongdoing after its first deployment

During the 2022 National AATTAP-AIIC Virtual Symposium, Lieutenant Stacie Lick of the Gloucester County, New Jersey, Prosecutor’s Office, discussed a case representing both the pinnacle of her work as the county’s CART Coordinator – and a painful test of her leadership abilities.

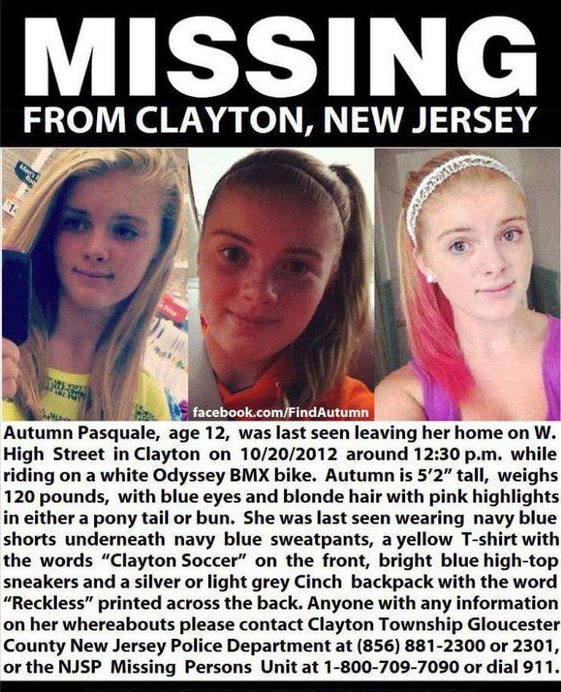

The case unfolded on October 20, 2012 – set to be one of most festive days in the small town of Clayton, New Jersey, 10 miles south of Philadelphia. While many in the town were cheering on Clayton High School’s afternoon homecoming game and evening dance, 12‐year‐old Autumn Pasquale was focused on outfitting the Odyssey BMX bike she had received for her 13th birthday, only nine days away.

While her family went to the game, Autumn said she would be working on her bike. But after her family returned home, Autumn was not there. Her 8 p.m. curfew passed, with no word from her. Autumn’s father, Anthony Pasquale, began calling friends to locate her, but some were at the dance, and others didn’t know her whereabouts. At 9:32 p.m. he called the Clayton Police Department to report her missing.

The responding officer visited the homecoming dance, confirming she was not there. The officer then interviewed some of Autumn’s friends. One told him that Autumn had planned to meet a guy named Justin, someone she had met online who offered to help her accessorize her bike. Friends also told police she was unhappy at home, perhaps even suicidal. Autumn and her father recently had moved into a house belonging to her father’s girlfriend and her family, with whom Autumn didn’t get along. Meanwhile, detectives pinged Autumn’s phone, which appeared to be in the vicinity of a local park. By 11:50 p.m., Autumn’s case was entered into the National Crime Information Center (NCIC) database as a missing person, with a ‘runaway’ code applied.

“There were no obvious indications that Autumn had been abducted or was in danger. Neither her bike nor other personal items were located or found abandoned, and there were no emergency calls or texts from her phone,” Lick said. “If there had been, that would have immediately changed the focus of the investigation.”

The next day, the Clayton Police Department realized they had not followed the state mandate to request a CART activation – required for any missing child under age 13.

Nevertheless, Lick and her partner Bryn Wilden began to put their CART planning work into action. “Bryn and I were tasked with creating its policies and procedures three years earlier, and were proud of what we accomplished,” Lick said. “But the CART had never been fully activated. We just kept telling ourselves we had a well thought-through plan in place, so it should work.”

The plan did work, but not without some detours and hurdles that at times struck Lick as “surreal.” Before those moments, however, 56 members of the 75-member team immediately showed up to assist. “And before long 150 officers were there. Once word went out in our county that there was a missing girl, people came from everywhere, and all wanted something to do,” she said. “That was great.”

A command post was set up, with a detective placed in charge of leads and sign-ins. The Clayton Police Department worked with the non-profit agency “A Child is Missing” to send reverse 911 calls. Lick’s team enlisted the help of parole officers who were able to search the homes of 63 sex offenders in the area (since under New Jersey’s “Megan’s Law,” offenders are on parole supervision for life, so no warrant is needed). Officers were investigating the mysterious “Justin” that Autumn was supposed to meet, and a volunteer K9 handler arrived with his bloodhound from Cape May, an hour and a half away.

Since Autumn was active on Facebook, detectives were able to access messages between her and a Justin Robinson and observed that the messages had become sexually explicit in the days leading up to Autumn’s disappearance. Had he abducted her? Or had she run away with him because she was unhappy at home?

“Autumn’s Facebook postings focused very much on her bike, while Justin’s took a more sexual tone, so she may have ignored any sixth-sense warning about meeting him. She was so proud of her bike and just wanted to modify it,” Lick said.

At the command post, a Clayton Police Detective who had been off the weekend before noticed Justin Robinson’s name on a big white Post-it note on the leads wall.

The detective mentioned that Justin’s brother, Dante, had once been arrested for sexual assault. That led the brothers to being brought to the station by their mother, and after separate interviews with them revealed suspicious answers, a search warrant was executed for the Robinson residence. There, detectives noticed a rolling recycling container had made heavy tracks as it was pulled from the boys’ home to an abandoned building next door.

Upon inspecting the bin, Autumn’s body was found; the county coroner would determine she died from blunt force trauma and strangulation. Inside the house, police discovered Autumn’s bike hidden beneath the basement stairs and her phone taped behind a toilet. In a concealed duffle bag, they found Autumn’s pants, soaked in urine, along with her shoes and a large knife.

“From the time she was reported missing to the time she was recovered, it was just over 48 hours,” Lick said. “We wish we could have found Autumn alive, but we were glad to have brought closure to the case.” Justin confessed to killing Autumn for her bike, and his brother Dante admitted assisting in the cover-up. On September 12, 2013, Justin accepted a plea deal for aggravated manslaughter and was sentenced to 17 years in prison. Dante pleaded guilty to fourth degree obstruction of justice and sentenced to 11 months in jail.

One might expect the case to have moved through closure at this point. However, Autumn’s father sued the Gloucester County Prosecutor's Office, the New Jersey State Police, and local law enforcement agencies, claiming investigators bungled the search and missed an opportunity to save his daughter. The case was later dismissed. “We couldn’t prevent the death of Autumn Pasquale because she was killed approximately six hours before she was ever reported missing,” Prosecutor Sean Dalton later stated.

“So much happened during that case that we learned from,” Lick said. “The one thing that saved us was our CART protocol. I tell everyone this: Have a CART policy and procedure in place and follow it. Because we did that, we were cleared of any wrongdoing.”

Case Lessons

- Control your volunteers. “Have a plan regarding what they will do. Because we didn’t, we lost control of them,” Lick recalled, noting that their volunteer K9 handler enlisted his own group of volunteers and went rogue. “The handler started his own command post and was giving out assignments,” she said. They showed up at a house the handler believed Autumn was in, busted the door down to gain access, but didn’t find the girl. The local police had to respond and de-escalate the situation. That was a very unwelcome and unnecessary distraction,” Lick said, adding with a smile, “We now have our own search dog.”

- Document everything. “One thing helpful is to have a sign-in sheet, where every officer must sign in with their name and contact information. We also had an assignment log that tracked every assignment – the date, time, and assignment given, whether it was completed, and a summary of what happened.” During the litigation following the case, “That log proved to be the best thing that we ever did.”

- Have a leads management system. “We had a psychic call and say Autumn could be found a field of wheat. We received a tip from a woman who said she saw a girl matching Autumn’s description get into a car with her son. Another person found a cell phone 20 miles away,” Lick said. “We needed that leads management system to keep track of it all.”

- Avoid one-size-fits-all emergency planning: “During the case, a member of our county Emergency Management team got up and took control of the Incident Command Center, treating the case as if he were managing a natural disaster,” Lick said. “I’ll never forget our State Police commander walking over to the white board and erasing the complicated strategy the man had just written out. The commander said, ‘Let me give you this advice: Only search if you’re truly looking for something – if you have a reason why people should be in an area.’ So that’s what we did.”

- Learn from your mistakes. “I’m not ashamed of the things that went wrong,” Lick said, “but I am proud we took those mistakes and used them as a model for what we now have in place.”

- Be aware that the media is everywhere. After finding Autumn’s body in the recycling bin, “out of respect for her and her family, we came up with a plan to have a trash removal truck take the body in the container to where we needed it go,” Lick said. “It was a way to avoid disrespectful coverage.”

- Have a victim advocate on your team. “We had a friendly, caring officer assist the family, but realized later how beneficial it would have to have a victim advocate. We now have one respond with us during a CART activation. That makes a big difference.”

(Credit: Facebook)